Notable Quotes: Excerpts from "Blurred Lines" by N. Bates

Edited by E. H. Sutton

Bates: Notable Quotes The following are excerpts quoted directly from “Blurred Lines: African American Community, Memory and Preservation in the Southwest Mountain Rural Historic District”, by Niya M. Bates, Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Dept. of Architectural History of the School of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Architectural History. April 2015. Footnotes copied here refer to images and references in the Bates document, available online: https://libraetd.lib.virginia.edu/public_view/j6731387r

For more information about Ms. Bates visit: https://history.princeton.edu/people/niya-bates

Overview of the Keswick area:

p.16 Churches, especially Baptist churches, were spaces where rural African Americans could practice their faith, hold community meetings and events, and conduct business.18

p.20 The primary focus of this thesis project is the community, memory, and preservation of the rural African American communities on the eastern side of the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District. African Americans and their families have been in this area for as long as it has been settled. In some cases, enslaved people inhabited the land prior to their white owners. However, the historic district as it currently exists, does not include the majority of historic black communities.

For many reasons, this area has enjoyed an unprecedented level of stability. Many of the African American families that currently live in the historic neighborhoods radiating from the northeastern side of Route 231 have been there for more than a century creating a stable, close-knit community. Black children raised in the era prior to desegregation benefitted from the presence of Rosenwald schools and teachers dedicated to providing lessons in History, English, Math, and various manual trades. Adults were able to find employment within walking distance of their homes. Most of the families in the African American neighborhoods were members of Zion Hill Baptist Church, St. John Baptist Church, or Union Grove Baptist Church. Not all of these conditions existed in other rural African American communities during the first half of the 20th century. Bonded by common work environments, religious practices, and personal relationships, the African American communities in Keswick have persevered through adversity in the Jim Crow South.

Black neighborhoods in the historic community of Cismont are representative of similar rural, and often unincorporated, African American settlements across the state of Virginia. Unlike communities in the Deep South where education and employment opportunities for rural Blacks were few and far between, these communities benefitted from less restrictive and somewhat progressive politics in Virginia. Still, locating the history of the African Americans in this historic district has been no easy task. The most reliable sources of information on these African American communities survives in oral history, collective memory, and church records. Sources of formal documentary information consulted in the process of this thesis project include local tax records, court documents, genealogical databases, census data, and print media archives.21

21 Property Deeds, Plats, Tax Record and Chancery Records can be retrieved at the Albemarle County Clerk’s Office Records Room. 2nd Floor. J.F. Bell Funeral Home has published a digital catalog of their burials beginning in the early twentieth century. The Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society holds a number of maps, photographs, and recordings specific to local history. The best information about cultural heritage in rural Black communities is passed through oral history and church records. The University of Virginia Special Collections Library is also a repository for local history.

Tracing the genealogies of various African American families was complicated because surnames of enslaved people were not often recorded in antebellum records. Furthermore, at the end of the Civil War many enslaved individuals adopted the surnames of their former owners, chose a name they liked, or switched from one name to another. Thus, tracking property ownership has been challenging. Another difficulty has been identifying exactly where properties were located in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Albemarle County court records. Taxes were recorded by a general distance from the courthouse rather than by a specific physical address. Many African American families at the turn of the century also raised children that were not their own with no formal adoption records or paper trail. Tracking down those individuals was most difficult, but could be traced through census records from family to family. Lastly, because so much of the history is preserved orally, the age and health of some of the oldest surviving members of the communities covered in this thesis became a significant hindrance. Two members of the community who were very helpful in providing me with information passed during the research process. While there are other surviving elders, several of them have been diagnosed with memory-related illnesses and their accounts of the neighborhood can be just as much fiction as fact; separating the fact from the fiction and hyperbole has been arduous.

On the early history of Keswick community:

p.24 While the modern postal zip code is quite sprawling, including roughly 50 square miles of land area centered about the Keswick Post Office, locals identify Keswick as the area nestled on the east side of the Southwest Mountains (see fig.2). This area includes many smaller unincorporated communities with names like Cobham, Cash Corner, and Cismont. Cismont was originally called Bowlesville, after a local Blacksmith, but it was renamed in the 1890s after Nicholas Meriwether’s Cismont Manor home “on the side of the mountain” nearby.23

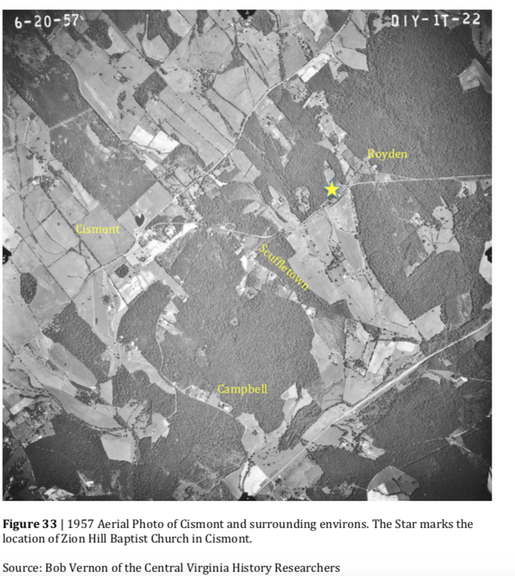

p.25 Several historic African American neighborhoods lie within the communities listed above and have unofficial names like: Bunker Hill, Clarks Tract, Scuffletown, Boyden, and Cobham. Ebenezer Boyden allowed to freedmen to construct cabins on his property near Zion Hill Road. George Bates described the same location and called it Kizzie Town. Deeds and other texts show that Ebenezer Boyden owned that property, called Hopedale, but there is no evidence that the Black settlement there was called Boyden Town or Kizzie Town.) Despite this fact, only one of these neighborhoods is included within the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District. In order to understand the current condition of the African American neighborhoods, it is necessary to study their beginnings as Virginia’s westernmost frontier.

Fry Jefferson Map shows colonists had settled in the Southwest Mountains area as early as 1751 (see fig. 3).25 Since then, generations of their families have cultivated the fertile land and built large estate homes, some former plantations.

p.26 In colonial Albemarle, most of the planters moving into the area came from the Tidewater region where tobacco and swidden agriculture had made them very wealthy men. This type of agriculture relied upon a very large enslaved labor force, which by the mid-eighteenth century was almost exclusively based on race. Enslaved Africans soon outnumbered whites 9600 to 8500 by the 1810 Census.31 However, tobacco was not well suited to growing in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and the planter elite found themselves experimenting with new crops. Changes in agricultural production in Albemarle reduced the number of laborers needed to cultivate crops on most plantations. An overabundance of enslaved people and Revolutionary ideals of freedom and universal rights inspired many slaveholders to manumit their slaves, either in life or through their wills at death. This dramatically increased the size of Albemarle County’s free Black population.32

p.27 Whether free or enslaved, Blacks living in the Southwest Mountains region in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries lived lives fraught with uncertainty. For slaves, their living environment was an embodiment of their fragile position in the plantation environment. … With little hope of long-term residency on any one plantation, or secure personal connections, the log cabins scattered at the base of the Southwest Mountains region became the physical embodiment of its enslaved inhabitants— anonymous and uncomfortable, but an integral part of the Cismont landscape (see fig. 4).

P. 32 James Hunter Terrell was born in 1832 and was the only son of Margaret Douglass Meriwether and Charles Terrell. James H. Terrell married a widow, but the couple never had children. However, the couple had over 80 slaves at their Music Hall plantation (see fig. 7). In death, James H. Terrell freed all of his slaves on the condition that they would move to Liberia as part of the Liberian Colonization Society experiment. From 1857 to 1866, Terrell’s former slaves wrote a series of letters to Dr. James Minor, executor of Terrell’s estate and Louisa Minor’s brother, with tales of their journey to Liberia, experience upon arrival, sicknesses and deaths, and industry. While these letters revealed many things about Liberia, they provided just as much insight into the lives and families of enslaved people in Cismont.

p.35 some enslaved people in Albemarle County used informal spaces for religious worship; they were willing to risk severe punishment in order to do so.

Other slaves in the Southwest Mountains area attended religious ceremonies alongside their masters. Many of the slaveholding families in Cismont attended Grace Episcopal Church. However, Blacks were not allowed to attend the church and instead they met outside or in their own cabins. If someone wanted to be baptized, then that person would go to their master and make a request. In March of 1856, Louisa Minor recorded in her diary:

“A beautiful day. Go to church to hear Bishop Johns again.... Uncle Hatter was confirmed today. He is Mr. Meade's first colored member and I believe him to be truly pious... My only regret is that Miss V and Lizzie Dee could not be with us. Have the "quality" [slave workers from the community] to dine with us as they are busy on the new road.64 “

p.36 “some slaveowners in the area allowed enslaved men to preach to the other slaves. Enslaved preachers probably learned through observing services at their masters’ churches and then practiced amongst themselves. Although there are many more mentions of church services in her diary, perhaps the last one is most telling. During the Civil War, most of the men were gone to fight for the Confederacy and Uncle Hatter must have been an older enslaved man serving as a driver or butler. In her entry from October 5-11th 1862, Louisa Minor wrote, ”We cannot go to church as Uncle Hatter is so poorly. I have a meeting at Mammy Nelly's house with the darkies and enjoy it. Uncle Hatter and Uncle Gabriel have a warm discussion. I'm edified.”65

p.46-47 African Americans also purchased property from former masters or whites seeking financial security by selling off some of their acreage. In 1882, Albert Johnson purchased a tract of land adjacent to present day Clarks Tract Road from Francis Meriwether of Cismont Manor Farm (see fig. 13). Shortly before dying, Meriwether subdivided a section of her property that lay on the eastern side of Route 231 and sold those parcels to former slaves and tenants. 91 Albert Johnson was a very skilled house wright and carpenter and he constructed a large house for his family. Around 1896, before completing his first house, Johnson purchased a second tract of land adjacent to the first and began building another house for his extended family. Johnson’s homes stand directly across the road from Cismont Manor, his first home being the only extant house in the Rivanna District built for and by a black builder that fronts Route 231 (see fig. 14). His first house, Breezy Oaks, so aptly named for the oak trees Johnson planted surrounding the house, demarcates the historic black neighborhood on Clarks Tract road.92

The last means of acquiring land for newly freed blacks was by receiving it as a gift. Documentary evidence suggests that slaves were the primary source of labor in constructing Grace Episcopal Church. In the Vestry minutes for the Grace Church Building Committee, as well as in the Rives book, there is mention of hiring slave or colored laborers to complete the task of building the church for $1.00 to $1.50 per day after William Strickland’s original church burned in a fire in 1895.93 Even though Reverend Ebenezer Boyden and Reverend Edward Meade baptized and performed funeral rights for slaves and freedmen, Blacks were not welcome in services at the church.In 1870, John Armstrong Chaloner, owner of Merrie Mill plantation at the time, gave a portion of his land along Route 22 at the intersection of present-day Zion Hill Road, to the developing black community for them to construct their church. The Black congregation named the church Zion Hill Baptist Church it is still in use today and despite other alterations ringing its original bell (see fig. 15a-d). Zion Hill became the center of black life in Cismont attracting the services of Reverend Robert Hughes, a descendant of the Hughes Family at Monticello send to live at Edgehill after Thomas Jefferson died.94 The gift of land from one parishioner of Grace Church reflects sentiments that Alexander H.H. Stuart conveyed to University of Virginia graduates in 1866 as cited by Moore:

Let us remember that no blame attaches to the Negro. They were our nurses in childhood, the companions of our sports in boyhood, and our humble and faithful servants through life. Without any agency on their part, the ties that bound them to us have been rudely broken. Let us extend to them a helping hand in the hour of destitution...and we should spare no pains to improve their conditions and qualify them...for usefulness in our community.95

Stuart believed it prudent for whites to help get freedmen on their feet. The overall tone of pity and misogyny in his speech belies his noble intentions and reveals that the white elite felt blacks had little agency of their own— a contradiction given many freedmen had already purchased their own land and built their own institutions by the late 1860s.

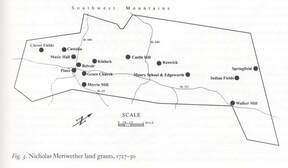

p. 49 Cloverfields Farm is one of the oldest homes along Route 231 and was the first estate of the Meriwether Family.101 In 1730, Nicholas Meriwether received land grant for 17,952, which encompassed most of the land along the South-West Mountains.102 Another Nicholas Meriwether I, who began constructing his home on the property during the mid 1700s, inherited this land.103 Descendants of Nicholas Meriwether have since owned or controlled several of the other extant historic farms along this mountain range including: Castalia, Kinloch, Edgehill, Cismont Manor, and Merrie Mill Farm.104

p. 50 As rural black villages materialized in Albemarle, former slaves and free born African Americans associated Federal and Greek revival houses with class, power, and control of the surrounding landscape. As such, Blacks who were able to afford larger houses adopted similar architectural aesthetics as their former owners, like the two-over- two carpenter’s gothic house that Harriet Johnson built near the aforementioned Dickinson House sometime around the 1880s (see fig.16). Middle class Blacks in Scuffletown built frame I-houses and four-squares. Others started with log cabins and expanded them as needed. Regardless of actual economic class, architecture was used to communicate the new social position of free Blacks and their identity as American citizens.107

Contrary to historical accounts of black rural communities being a collection of poorly organized shacks, by the 1940s the Maxfield Road neighborhood was neatly organized, had manicured gardens facing the road, and well-maintained outbuildings with riven hardwood or clapboard siding (see fig. 17).108 Families raised hogs and chickens and the back yard was a utilitarian space for penning livestock or foul, feeding animals, grazing chickens, butchering meat, and more.109 Kitchens were often at the rear of the house to keep the front rooms of the home reserved for living spaces and entertaining guests. It also enabled more efficient preparation of meals because it was closer to the garden and animal coops (see fig. 17b). One of the oldest African American homes in Scuffletown stands at the intersection of Maxfield Road and Louisa Rd. Originally owned by the Scott family, the house is representative of the houses of working-class African Americans in Cismont.

p.57-58 After building a community of houses, churches, and schools, African Americans had designed rural Neighborhoods that were physically and socially insulated. These places were subject to federal, state, and local judicial laws, but operated primarily on their own social and moral code. As St. John Training School alumnus, Horace Brooks, said in an interview for the Virginia Rosenwald Project, “Not only the teachers taught. Whoever you went to see, you were just like their children, too. They treat you all the same. When you grow up like that, you don't have no dealing with the law, 'cause you know the rules.”128 Practices that are no longer politically correct, like corporal punishment and prayer in school, were cherished aspects of Black rural life on which many elderly residents still reflect.

The relationship between the church and social lives of its members is critical to interpreting the history of this place. In the Scuffletown neighborhood on Maxfield Road, the separation between church and state was scant. Aside from federal census records, church rosters serve as some of the best way to identify the families that lived in the historically black neighborhoods (see Appendix B). Almost all of the residents were members of Zion Hill Baptist Church and in the early decades of the twentieth century, the same woman served as the teacher for the Cismont Training School and lead Sunday school at the church.129 Rebecca Boller remarked, “She taught Sunday school and she taught school, and-- I don't know-- it's kind of sad because I really don't know if she really knew what kind of impression she left.”130 Rebecca Boller’s admiration for her teacher testifies to the centrality of Zion Hill church in Black life in Cismont, but also to the role of community members in developing secular knowledge and religion in the youth. In an era when government funding was anything but equal for Black schools as it was for white schools in the same districts, religion and the Bible became intrinsic aspects of rural Black education because most families had one.131

p. 64 Of the two Rosenwald schools in this district, Cismont Training School and St. John School, neither is listed; both survive. The nomination for the district lists the “unnamed” black community along Route 647, Scuffletown, as a contributing resource exemplary of a traditional black settlement, but leaves out the other black environs.145 Those not mentioned in the nomination are: Cobham, Clarks Tract Road, Bunker Hill, Boyden, and Campbell. With the exception of the two Rosenwald Schools and two historically black churches, buildings that contribute to the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District portray the history of African Americans in the Southwest Mountains in piecemeal fashion.

The Blacks living in these communities were working and middle-class families. The settlement pattern of small lots, located on side streets or adjacent to larger estates, and centered around a church or school is consistent with postbellum Black neighborhoods that Jeff Werner has observed while working on other historic districts with the Piedmont Environment Council.146 The historical narrative of the Southwest Mountains district is one not only of slavery and elite plantations, but also reconstruction and negotiation of the new cultural landscape birthed by the Civil War.

The demise of Scuffletown, p. 70

In addition to being a side effect of unclear deeds, increased vacancy rates are a direct result of economic changes in rural communities. Whereas Scuffletown and similar rural black enclaves thrived when agricultural and manual trade skills were in high demand in the first half of the twentieth century, urban industrialization and manufacturing after World War II drew younger rural Blacks to northern cities. In Cismont, men like Landers Bates and Harry Byrd left their neighborhoods to go work at the Wonder Bread factory in Washington, D.C. Once they were established in the city, they served as conductors guiding other young men from Cismont to industrial jobs “up north” where they could make much more money than they could in rural Albemarle.161 According to the 2010 U.S. Census, people identifying as African American only composed 8.7 percent of the population in the Rivanna District.162 This number increases to 19.3 when those identifying as one race in combination with black and two or more races in combination with black are included in the total percentage. For a district that, in 1870, was majority African American, emigration to urban areas has caused major shifts in the demographics of working-class neighborhoods, and is very noticeable in rural communities. The brunt of that cultural loss likely occurred in the rural villages and not the larger properties.

On Preservation of the neighborhoods:

In 2007, the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors released a new Rural Areas Comprehensive Plan. The 48-page report gives detailed information about population, current land uses, development areas, land cover, waterways and other natural resources, traffic accidents, and lands in conservation. Concerns about water quality, development, and conservation fueled the development of this new comprehensive approach aimed at “an evolving commitment to growth management.”163 The comprehensive rural land use plan permanently connected the county’s rural conservation goals with its cultural and historic preservation plan, but does not make mention of African Americans or how to formally recognize culturally significant sites:

The County also has a rich archaeological heritage, having been occupied by Native Americans for approximately 12,000 years before the arrival of European settlers, who themselves left significant artifacts and sites.164

Once again, African Americans are excised from the historic record.

Land loss has already been addressed as one of the most significant preservation challenge in rural black communities. The county offers several different resources and programs for putting land in easement, yet these options usually require a minimum amount of land. For instance, a property owner would need at least ten, but more often than not something more like forty or more acres of land that could be put under conservation or open-space easement. Albemarle County has a program that seeks to protect open spaces from development. Zoning and other ordinances further protect rural lands from subdivision and other developments that would disrupt agriculture, scenery, or historic resources. However, there is little to no interest in conserving small rural tracts on the scale that property owners in Scuffletown and others would need. Albemarle County claims to want to help owners afford their land, but assumes that only owners with large tracts of land have an interest in environmental conservation.165 Homeowners with smaller parcels of lands cannot benefit from tax incentives as they are currently written and applied. Scuffletown and the other neighborhoods cannot take advantage of this approach further perpetuating the practice of privileging the elite. (163 Albemarle County Board of Supervisors, “Albemarle County Rural Area Plan” (Charlottesville: Board of Supervisors, 7 September 2007). PDF.

p. 73 At present, there are at least three resource-specific programs available to rural and minority communities. The first program is geared at protecting America’s rural agricultural heritage by encouraging farmers to maintain their barns and use them for modern agricultural purposes. A great program for other areas, Barn Again! would have little to no impact on this historic district because there are relatively few barns. This area, however, is rich in other agricultural outbuildings like stables, smokehouses, dairies, privies, chicken coops, etc.170

Another initiative is the Rosenwald School Initiative. The National Trust Website states:

The National Trust for Historic Preservation's Southern Office is leading

the Rosenwald Schools Initiative... Many communities are now seeking ways to adapt these historic structures—no longer used for schools—to serve new needs. The Lowe's Charitable and Educational Foundation is partnering with the National Trust for Historic Preservation to support the rehabilitation and restoration of Rosenwald Schools.171

There are two of these schools in the Cismont area in the eastern section of the historic district. Both have been repurposed—one as a private residence, after considerable alterations, and the other as a community center, with more sympathetic restorations. Based upon the geographic distribution of Rosenwald Schools throughout the rural south, these buildings could be repurposed to provide services currently clustered in urban areas. If two of the most obvious goals of historic preservation are to encourage economic development and promote a healthier population, as stated in Albemarle County’s comprehensive plan, then adaptive reuse of Rosenwald schools could be a viable tool for bringing services to struggling rural localities.

Call to Action for Preserving History p.77

Beyond preserving cultural traditions is ensuring that cultural memory of these rural Black neighborhoods can be recorded and archived for future generations. Black churches and schools have long been the repositories for photographs, burial records, and oral history of black communities. However, most black schools have long since shut their doors and faded from our collective memory. Many Rosenwald alumni are in their seventies, eighties, and nineties. As the elders of the community pass away, there are fewer and fewer residents to sustain black rural church congregations and no one is collecting historical records from these places before the communities die out completely. Because the state and local governments have benefitted the most from the labor of working-class blacks in rural areas, they have an ethical responsibility to preserve the cultural and material heritage in the historic district.

Need for signage, p. 78

The County should adopt a similar program for rural black neighborhoods and encourage property owners to organize neighborhood associations to govern capital projects that will improve the community.

The County of Albemarle should start a rural preservation initiative that aims to reclaim the colloquial names of rural neighborhoods by placing signage at the entrance corridor for each community. For example, a sign for Scuffletown with an approximate date of establishment could be placed at the intersection of Route 22 and Maxfield Road. The same could be done for the black neighborhoods at Bunker Hill, Clarks Tract, Boyden, Cobham, and Campbell. A project like this would require some documentary research to discover all of the former names that rural historic neighborhoods have, but the names on the signs should correlate with the period of significance for the Southwest Mountains rural Historic District. The County of Albemarle partner with the Central Virginia History Researchers of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center to conduct research and encourage community buy-in and involvement. Another tenant of this program could be to allow owners to purchase a plaque for each individual house that is located in a historic black rural community, much like century farm markers are used in Louisa County.

p. 81 “Rural black communities existed in the antebellum period and are a part of the same historical narrative as the former plantation houses that have been well served by building centric preservation policy. In order to preserve rural African American historic neighborhoods and architecture, we have to create language that celebrates cultural context and privileges people, narratives, and context over architecture. In a time when Black Americans are marching and rioting to affirm that Black Lives Matter, we should be looking to the historic physical landscapes around us and learning how to avoid perpetuating negative cultural stereotypes of rural African American life. “

(See Image of the Meriwether grant with names of the local farms. Ed Lay, Architecture of Jefferson Country p. 25)

For more information about Ms. Bates visit: https://history.princeton.edu/people/niya-bates

Overview of the Keswick area:

p.16 Churches, especially Baptist churches, were spaces where rural African Americans could practice their faith, hold community meetings and events, and conduct business.18

p.20 The primary focus of this thesis project is the community, memory, and preservation of the rural African American communities on the eastern side of the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District. African Americans and their families have been in this area for as long as it has been settled. In some cases, enslaved people inhabited the land prior to their white owners. However, the historic district as it currently exists, does not include the majority of historic black communities.

For many reasons, this area has enjoyed an unprecedented level of stability. Many of the African American families that currently live in the historic neighborhoods radiating from the northeastern side of Route 231 have been there for more than a century creating a stable, close-knit community. Black children raised in the era prior to desegregation benefitted from the presence of Rosenwald schools and teachers dedicated to providing lessons in History, English, Math, and various manual trades. Adults were able to find employment within walking distance of their homes. Most of the families in the African American neighborhoods were members of Zion Hill Baptist Church, St. John Baptist Church, or Union Grove Baptist Church. Not all of these conditions existed in other rural African American communities during the first half of the 20th century. Bonded by common work environments, religious practices, and personal relationships, the African American communities in Keswick have persevered through adversity in the Jim Crow South.

Black neighborhoods in the historic community of Cismont are representative of similar rural, and often unincorporated, African American settlements across the state of Virginia. Unlike communities in the Deep South where education and employment opportunities for rural Blacks were few and far between, these communities benefitted from less restrictive and somewhat progressive politics in Virginia. Still, locating the history of the African Americans in this historic district has been no easy task. The most reliable sources of information on these African American communities survives in oral history, collective memory, and church records. Sources of formal documentary information consulted in the process of this thesis project include local tax records, court documents, genealogical databases, census data, and print media archives.21

21 Property Deeds, Plats, Tax Record and Chancery Records can be retrieved at the Albemarle County Clerk’s Office Records Room. 2nd Floor. J.F. Bell Funeral Home has published a digital catalog of their burials beginning in the early twentieth century. The Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society holds a number of maps, photographs, and recordings specific to local history. The best information about cultural heritage in rural Black communities is passed through oral history and church records. The University of Virginia Special Collections Library is also a repository for local history.

Tracing the genealogies of various African American families was complicated because surnames of enslaved people were not often recorded in antebellum records. Furthermore, at the end of the Civil War many enslaved individuals adopted the surnames of their former owners, chose a name they liked, or switched from one name to another. Thus, tracking property ownership has been challenging. Another difficulty has been identifying exactly where properties were located in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Albemarle County court records. Taxes were recorded by a general distance from the courthouse rather than by a specific physical address. Many African American families at the turn of the century also raised children that were not their own with no formal adoption records or paper trail. Tracking down those individuals was most difficult, but could be traced through census records from family to family. Lastly, because so much of the history is preserved orally, the age and health of some of the oldest surviving members of the communities covered in this thesis became a significant hindrance. Two members of the community who were very helpful in providing me with information passed during the research process. While there are other surviving elders, several of them have been diagnosed with memory-related illnesses and their accounts of the neighborhood can be just as much fiction as fact; separating the fact from the fiction and hyperbole has been arduous.

On the early history of Keswick community:

p.24 While the modern postal zip code is quite sprawling, including roughly 50 square miles of land area centered about the Keswick Post Office, locals identify Keswick as the area nestled on the east side of the Southwest Mountains (see fig.2). This area includes many smaller unincorporated communities with names like Cobham, Cash Corner, and Cismont. Cismont was originally called Bowlesville, after a local Blacksmith, but it was renamed in the 1890s after Nicholas Meriwether’s Cismont Manor home “on the side of the mountain” nearby.23

p.25 Several historic African American neighborhoods lie within the communities listed above and have unofficial names like: Bunker Hill, Clarks Tract, Scuffletown, Boyden, and Cobham. Ebenezer Boyden allowed to freedmen to construct cabins on his property near Zion Hill Road. George Bates described the same location and called it Kizzie Town. Deeds and other texts show that Ebenezer Boyden owned that property, called Hopedale, but there is no evidence that the Black settlement there was called Boyden Town or Kizzie Town.) Despite this fact, only one of these neighborhoods is included within the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District. In order to understand the current condition of the African American neighborhoods, it is necessary to study their beginnings as Virginia’s westernmost frontier.

Fry Jefferson Map shows colonists had settled in the Southwest Mountains area as early as 1751 (see fig. 3).25 Since then, generations of their families have cultivated the fertile land and built large estate homes, some former plantations.

p.26 In colonial Albemarle, most of the planters moving into the area came from the Tidewater region where tobacco and swidden agriculture had made them very wealthy men. This type of agriculture relied upon a very large enslaved labor force, which by the mid-eighteenth century was almost exclusively based on race. Enslaved Africans soon outnumbered whites 9600 to 8500 by the 1810 Census.31 However, tobacco was not well suited to growing in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and the planter elite found themselves experimenting with new crops. Changes in agricultural production in Albemarle reduced the number of laborers needed to cultivate crops on most plantations. An overabundance of enslaved people and Revolutionary ideals of freedom and universal rights inspired many slaveholders to manumit their slaves, either in life or through their wills at death. This dramatically increased the size of Albemarle County’s free Black population.32

p.27 Whether free or enslaved, Blacks living in the Southwest Mountains region in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries lived lives fraught with uncertainty. For slaves, their living environment was an embodiment of their fragile position in the plantation environment. … With little hope of long-term residency on any one plantation, or secure personal connections, the log cabins scattered at the base of the Southwest Mountains region became the physical embodiment of its enslaved inhabitants— anonymous and uncomfortable, but an integral part of the Cismont landscape (see fig. 4).

P. 32 James Hunter Terrell was born in 1832 and was the only son of Margaret Douglass Meriwether and Charles Terrell. James H. Terrell married a widow, but the couple never had children. However, the couple had over 80 slaves at their Music Hall plantation (see fig. 7). In death, James H. Terrell freed all of his slaves on the condition that they would move to Liberia as part of the Liberian Colonization Society experiment. From 1857 to 1866, Terrell’s former slaves wrote a series of letters to Dr. James Minor, executor of Terrell’s estate and Louisa Minor’s brother, with tales of their journey to Liberia, experience upon arrival, sicknesses and deaths, and industry. While these letters revealed many things about Liberia, they provided just as much insight into the lives and families of enslaved people in Cismont.

p.35 some enslaved people in Albemarle County used informal spaces for religious worship; they were willing to risk severe punishment in order to do so.

Other slaves in the Southwest Mountains area attended religious ceremonies alongside their masters. Many of the slaveholding families in Cismont attended Grace Episcopal Church. However, Blacks were not allowed to attend the church and instead they met outside or in their own cabins. If someone wanted to be baptized, then that person would go to their master and make a request. In March of 1856, Louisa Minor recorded in her diary:

“A beautiful day. Go to church to hear Bishop Johns again.... Uncle Hatter was confirmed today. He is Mr. Meade's first colored member and I believe him to be truly pious... My only regret is that Miss V and Lizzie Dee could not be with us. Have the "quality" [slave workers from the community] to dine with us as they are busy on the new road.64 “

p.36 “some slaveowners in the area allowed enslaved men to preach to the other slaves. Enslaved preachers probably learned through observing services at their masters’ churches and then practiced amongst themselves. Although there are many more mentions of church services in her diary, perhaps the last one is most telling. During the Civil War, most of the men were gone to fight for the Confederacy and Uncle Hatter must have been an older enslaved man serving as a driver or butler. In her entry from October 5-11th 1862, Louisa Minor wrote, ”We cannot go to church as Uncle Hatter is so poorly. I have a meeting at Mammy Nelly's house with the darkies and enjoy it. Uncle Hatter and Uncle Gabriel have a warm discussion. I'm edified.”65

p.46-47 African Americans also purchased property from former masters or whites seeking financial security by selling off some of their acreage. In 1882, Albert Johnson purchased a tract of land adjacent to present day Clarks Tract Road from Francis Meriwether of Cismont Manor Farm (see fig. 13). Shortly before dying, Meriwether subdivided a section of her property that lay on the eastern side of Route 231 and sold those parcels to former slaves and tenants. 91 Albert Johnson was a very skilled house wright and carpenter and he constructed a large house for his family. Around 1896, before completing his first house, Johnson purchased a second tract of land adjacent to the first and began building another house for his extended family. Johnson’s homes stand directly across the road from Cismont Manor, his first home being the only extant house in the Rivanna District built for and by a black builder that fronts Route 231 (see fig. 14). His first house, Breezy Oaks, so aptly named for the oak trees Johnson planted surrounding the house, demarcates the historic black neighborhood on Clarks Tract road.92

The last means of acquiring land for newly freed blacks was by receiving it as a gift. Documentary evidence suggests that slaves were the primary source of labor in constructing Grace Episcopal Church. In the Vestry minutes for the Grace Church Building Committee, as well as in the Rives book, there is mention of hiring slave or colored laborers to complete the task of building the church for $1.00 to $1.50 per day after William Strickland’s original church burned in a fire in 1895.93 Even though Reverend Ebenezer Boyden and Reverend Edward Meade baptized and performed funeral rights for slaves and freedmen, Blacks were not welcome in services at the church.In 1870, John Armstrong Chaloner, owner of Merrie Mill plantation at the time, gave a portion of his land along Route 22 at the intersection of present-day Zion Hill Road, to the developing black community for them to construct their church. The Black congregation named the church Zion Hill Baptist Church it is still in use today and despite other alterations ringing its original bell (see fig. 15a-d). Zion Hill became the center of black life in Cismont attracting the services of Reverend Robert Hughes, a descendant of the Hughes Family at Monticello send to live at Edgehill after Thomas Jefferson died.94 The gift of land from one parishioner of Grace Church reflects sentiments that Alexander H.H. Stuart conveyed to University of Virginia graduates in 1866 as cited by Moore:

Let us remember that no blame attaches to the Negro. They were our nurses in childhood, the companions of our sports in boyhood, and our humble and faithful servants through life. Without any agency on their part, the ties that bound them to us have been rudely broken. Let us extend to them a helping hand in the hour of destitution...and we should spare no pains to improve their conditions and qualify them...for usefulness in our community.95

Stuart believed it prudent for whites to help get freedmen on their feet. The overall tone of pity and misogyny in his speech belies his noble intentions and reveals that the white elite felt blacks had little agency of their own— a contradiction given many freedmen had already purchased their own land and built their own institutions by the late 1860s.

p. 49 Cloverfields Farm is one of the oldest homes along Route 231 and was the first estate of the Meriwether Family.101 In 1730, Nicholas Meriwether received land grant for 17,952, which encompassed most of the land along the South-West Mountains.102 Another Nicholas Meriwether I, who began constructing his home on the property during the mid 1700s, inherited this land.103 Descendants of Nicholas Meriwether have since owned or controlled several of the other extant historic farms along this mountain range including: Castalia, Kinloch, Edgehill, Cismont Manor, and Merrie Mill Farm.104

p. 50 As rural black villages materialized in Albemarle, former slaves and free born African Americans associated Federal and Greek revival houses with class, power, and control of the surrounding landscape. As such, Blacks who were able to afford larger houses adopted similar architectural aesthetics as their former owners, like the two-over- two carpenter’s gothic house that Harriet Johnson built near the aforementioned Dickinson House sometime around the 1880s (see fig.16). Middle class Blacks in Scuffletown built frame I-houses and four-squares. Others started with log cabins and expanded them as needed. Regardless of actual economic class, architecture was used to communicate the new social position of free Blacks and their identity as American citizens.107

Contrary to historical accounts of black rural communities being a collection of poorly organized shacks, by the 1940s the Maxfield Road neighborhood was neatly organized, had manicured gardens facing the road, and well-maintained outbuildings with riven hardwood or clapboard siding (see fig. 17).108 Families raised hogs and chickens and the back yard was a utilitarian space for penning livestock or foul, feeding animals, grazing chickens, butchering meat, and more.109 Kitchens were often at the rear of the house to keep the front rooms of the home reserved for living spaces and entertaining guests. It also enabled more efficient preparation of meals because it was closer to the garden and animal coops (see fig. 17b). One of the oldest African American homes in Scuffletown stands at the intersection of Maxfield Road and Louisa Rd. Originally owned by the Scott family, the house is representative of the houses of working-class African Americans in Cismont.

p.57-58 After building a community of houses, churches, and schools, African Americans had designed rural Neighborhoods that were physically and socially insulated. These places were subject to federal, state, and local judicial laws, but operated primarily on their own social and moral code. As St. John Training School alumnus, Horace Brooks, said in an interview for the Virginia Rosenwald Project, “Not only the teachers taught. Whoever you went to see, you were just like their children, too. They treat you all the same. When you grow up like that, you don't have no dealing with the law, 'cause you know the rules.”128 Practices that are no longer politically correct, like corporal punishment and prayer in school, were cherished aspects of Black rural life on which many elderly residents still reflect.

The relationship between the church and social lives of its members is critical to interpreting the history of this place. In the Scuffletown neighborhood on Maxfield Road, the separation between church and state was scant. Aside from federal census records, church rosters serve as some of the best way to identify the families that lived in the historically black neighborhoods (see Appendix B). Almost all of the residents were members of Zion Hill Baptist Church and in the early decades of the twentieth century, the same woman served as the teacher for the Cismont Training School and lead Sunday school at the church.129 Rebecca Boller remarked, “She taught Sunday school and she taught school, and-- I don't know-- it's kind of sad because I really don't know if she really knew what kind of impression she left.”130 Rebecca Boller’s admiration for her teacher testifies to the centrality of Zion Hill church in Black life in Cismont, but also to the role of community members in developing secular knowledge and religion in the youth. In an era when government funding was anything but equal for Black schools as it was for white schools in the same districts, religion and the Bible became intrinsic aspects of rural Black education because most families had one.131

p. 64 Of the two Rosenwald schools in this district, Cismont Training School and St. John School, neither is listed; both survive. The nomination for the district lists the “unnamed” black community along Route 647, Scuffletown, as a contributing resource exemplary of a traditional black settlement, but leaves out the other black environs.145 Those not mentioned in the nomination are: Cobham, Clarks Tract Road, Bunker Hill, Boyden, and Campbell. With the exception of the two Rosenwald Schools and two historically black churches, buildings that contribute to the Southwest Mountains Rural Historic District portray the history of African Americans in the Southwest Mountains in piecemeal fashion.

The Blacks living in these communities were working and middle-class families. The settlement pattern of small lots, located on side streets or adjacent to larger estates, and centered around a church or school is consistent with postbellum Black neighborhoods that Jeff Werner has observed while working on other historic districts with the Piedmont Environment Council.146 The historical narrative of the Southwest Mountains district is one not only of slavery and elite plantations, but also reconstruction and negotiation of the new cultural landscape birthed by the Civil War.

The demise of Scuffletown, p. 70

In addition to being a side effect of unclear deeds, increased vacancy rates are a direct result of economic changes in rural communities. Whereas Scuffletown and similar rural black enclaves thrived when agricultural and manual trade skills were in high demand in the first half of the twentieth century, urban industrialization and manufacturing after World War II drew younger rural Blacks to northern cities. In Cismont, men like Landers Bates and Harry Byrd left their neighborhoods to go work at the Wonder Bread factory in Washington, D.C. Once they were established in the city, they served as conductors guiding other young men from Cismont to industrial jobs “up north” where they could make much more money than they could in rural Albemarle.161 According to the 2010 U.S. Census, people identifying as African American only composed 8.7 percent of the population in the Rivanna District.162 This number increases to 19.3 when those identifying as one race in combination with black and two or more races in combination with black are included in the total percentage. For a district that, in 1870, was majority African American, emigration to urban areas has caused major shifts in the demographics of working-class neighborhoods, and is very noticeable in rural communities. The brunt of that cultural loss likely occurred in the rural villages and not the larger properties.

On Preservation of the neighborhoods:

In 2007, the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors released a new Rural Areas Comprehensive Plan. The 48-page report gives detailed information about population, current land uses, development areas, land cover, waterways and other natural resources, traffic accidents, and lands in conservation. Concerns about water quality, development, and conservation fueled the development of this new comprehensive approach aimed at “an evolving commitment to growth management.”163 The comprehensive rural land use plan permanently connected the county’s rural conservation goals with its cultural and historic preservation plan, but does not make mention of African Americans or how to formally recognize culturally significant sites:

The County also has a rich archaeological heritage, having been occupied by Native Americans for approximately 12,000 years before the arrival of European settlers, who themselves left significant artifacts and sites.164

Once again, African Americans are excised from the historic record.

Land loss has already been addressed as one of the most significant preservation challenge in rural black communities. The county offers several different resources and programs for putting land in easement, yet these options usually require a minimum amount of land. For instance, a property owner would need at least ten, but more often than not something more like forty or more acres of land that could be put under conservation or open-space easement. Albemarle County has a program that seeks to protect open spaces from development. Zoning and other ordinances further protect rural lands from subdivision and other developments that would disrupt agriculture, scenery, or historic resources. However, there is little to no interest in conserving small rural tracts on the scale that property owners in Scuffletown and others would need. Albemarle County claims to want to help owners afford their land, but assumes that only owners with large tracts of land have an interest in environmental conservation.165 Homeowners with smaller parcels of lands cannot benefit from tax incentives as they are currently written and applied. Scuffletown and the other neighborhoods cannot take advantage of this approach further perpetuating the practice of privileging the elite. (163 Albemarle County Board of Supervisors, “Albemarle County Rural Area Plan” (Charlottesville: Board of Supervisors, 7 September 2007). PDF.

p. 73 At present, there are at least three resource-specific programs available to rural and minority communities. The first program is geared at protecting America’s rural agricultural heritage by encouraging farmers to maintain their barns and use them for modern agricultural purposes. A great program for other areas, Barn Again! would have little to no impact on this historic district because there are relatively few barns. This area, however, is rich in other agricultural outbuildings like stables, smokehouses, dairies, privies, chicken coops, etc.170

Another initiative is the Rosenwald School Initiative. The National Trust Website states:

The National Trust for Historic Preservation's Southern Office is leading

the Rosenwald Schools Initiative... Many communities are now seeking ways to adapt these historic structures—no longer used for schools—to serve new needs. The Lowe's Charitable and Educational Foundation is partnering with the National Trust for Historic Preservation to support the rehabilitation and restoration of Rosenwald Schools.171

There are two of these schools in the Cismont area in the eastern section of the historic district. Both have been repurposed—one as a private residence, after considerable alterations, and the other as a community center, with more sympathetic restorations. Based upon the geographic distribution of Rosenwald Schools throughout the rural south, these buildings could be repurposed to provide services currently clustered in urban areas. If two of the most obvious goals of historic preservation are to encourage economic development and promote a healthier population, as stated in Albemarle County’s comprehensive plan, then adaptive reuse of Rosenwald schools could be a viable tool for bringing services to struggling rural localities.

Call to Action for Preserving History p.77

Beyond preserving cultural traditions is ensuring that cultural memory of these rural Black neighborhoods can be recorded and archived for future generations. Black churches and schools have long been the repositories for photographs, burial records, and oral history of black communities. However, most black schools have long since shut their doors and faded from our collective memory. Many Rosenwald alumni are in their seventies, eighties, and nineties. As the elders of the community pass away, there are fewer and fewer residents to sustain black rural church congregations and no one is collecting historical records from these places before the communities die out completely. Because the state and local governments have benefitted the most from the labor of working-class blacks in rural areas, they have an ethical responsibility to preserve the cultural and material heritage in the historic district.

Need for signage, p. 78

The County should adopt a similar program for rural black neighborhoods and encourage property owners to organize neighborhood associations to govern capital projects that will improve the community.

The County of Albemarle should start a rural preservation initiative that aims to reclaim the colloquial names of rural neighborhoods by placing signage at the entrance corridor for each community. For example, a sign for Scuffletown with an approximate date of establishment could be placed at the intersection of Route 22 and Maxfield Road. The same could be done for the black neighborhoods at Bunker Hill, Clarks Tract, Boyden, Cobham, and Campbell. A project like this would require some documentary research to discover all of the former names that rural historic neighborhoods have, but the names on the signs should correlate with the period of significance for the Southwest Mountains rural Historic District. The County of Albemarle partner with the Central Virginia History Researchers of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center to conduct research and encourage community buy-in and involvement. Another tenant of this program could be to allow owners to purchase a plaque for each individual house that is located in a historic black rural community, much like century farm markers are used in Louisa County.

p. 81 “Rural black communities existed in the antebellum period and are a part of the same historical narrative as the former plantation houses that have been well served by building centric preservation policy. In order to preserve rural African American historic neighborhoods and architecture, we have to create language that celebrates cultural context and privileges people, narratives, and context over architecture. In a time when Black Americans are marching and rioting to affirm that Black Lives Matter, we should be looking to the historic physical landscapes around us and learning how to avoid perpetuating negative cultural stereotypes of rural African American life. “

(See Image of the Meriwether grant with names of the local farms. Ed Lay, Architecture of Jefferson Country p. 25)